Agriculture and negative externalities

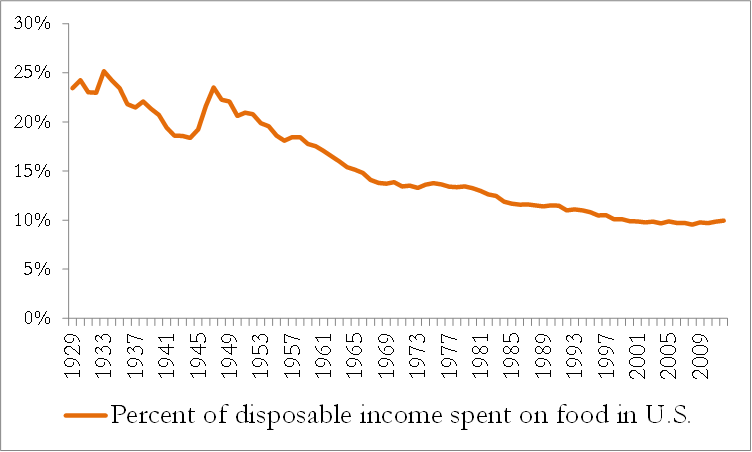

Most agricultural controversies are social, not personal issues. Animal welfare, carbon footprints, and water pollution are all issues that call for social activism and/or governmental policy. Consider the percent of disposable (i.e., after-tax) income Americans spend on food below. In the 1930s we spent over 20% of this income on food, while now we spend less than 15%.

Figure 1—Percent of income spent on food over time

That is a remarkable achievement, but food activists beckon us to pause and first consider whether the percentage would really fall if we included all the “other” costs not included in the grocery store price. Perhaps our health care costs have risen due to pesticide use, and the percent in Figure 1 would have risen if food prices reflected that cost. Does the grocery store price include the potential burden we place on future generations by not confronting global warming? Does the grocery store price of chicken account for the additional expenses the City of Tulsa must pay to purify their water? If not, then the price of food is not really as low as it appears in the store.

Quotation 1—Michael Pollon on cheap food

Cheap food is an illusion. There is no such thing as cheap food. The real cost of the food is paid somewhere, and if it isn’t paid at the cash register it’s paid, you know, it’s charged to the environment, it’s charged to the public purse in the form of subsidies, and it’s charged to your health.

—Michael Pollan in the documentary Fresh, 2012 (36:45).

We don’t pay the cost of soil erosion. Future generations do, so a low grocery store price in this sense is subsidized by future generations. Animal advocates would claim that livestock subsidize our food, if livestock farms reduce their cost of production by treating their animals poorly.

All of these “hidden” costs are formally referred to by economists as externalities, which is a cost or benefit that affects a party who did not consent to that cost or benefit; or, a cost or benefit of a good that is not reflected in the good’s price. Neither definition probably means much to you, so a few examples would be helpful.

- Farmers use energy to create greenhouse tomatoes. That energy use is a cost, but it is not an externality. The farmer consents to paying the energy price because he knows you are willing to pay the price of the tomatoes he sells. The person selling the energy to the farmer also consented to its use or she never would have sold it in the first place. Everyone consents to the use of the energy in tomato production. There is no cost or benefit here that people do not consent to, so no externality exists.

- Recall the article The poultry manure blame-game, which describes how applications of broiler manure to cropland are polluting Oklahoma rivers and lakes. When buying a chicken the consumer pays one price at the grocery store, but an additional cost if a lake they visit is too polluted to use. The problem is that the consumer is largely unaware of the pollution caused by her chicken purchase, and the chicken producer is not charged for the pollution she causes. Chicken prices do not rise as water pollution increases. In reality, the opposite may occur. This pollution cost is therefore is an externality.

- Carbon emissions and soil erosion might seriously impact the lives of future generations, but those individuals in the future did not consent to subsidizing our food, so carbon emissions and soil erosion can be considered externalities as well.

- Externalities are not always bad things. There are negative externalities like those described above, and there are positive externalities. A good example of a positive externality is the practice of no-till farming, where farmers no longer pierce the ground with plows. Plowing increases soil erosion, so as farmers have increasingly adopted no-till farming they reduce erosion and thus improve future generations’ ability to feed themselves. Because these future generations did not subsidize the practice, that benefit is not reflected in the price of no-till equipment.

- Negative externalities should be discouraged, and positive externalities, encouraged. This is why we tell lawmakers to regulate broiler manure applications and subsidize research in no-till farming. Of course, no-till farming could be thought of as a positive externality or the prevention of a negative externality, but this is true of all externalities. The negative / positive distinction is really a matter of semantics, and for this reason, I frame all externalities as a form of negative externalities.

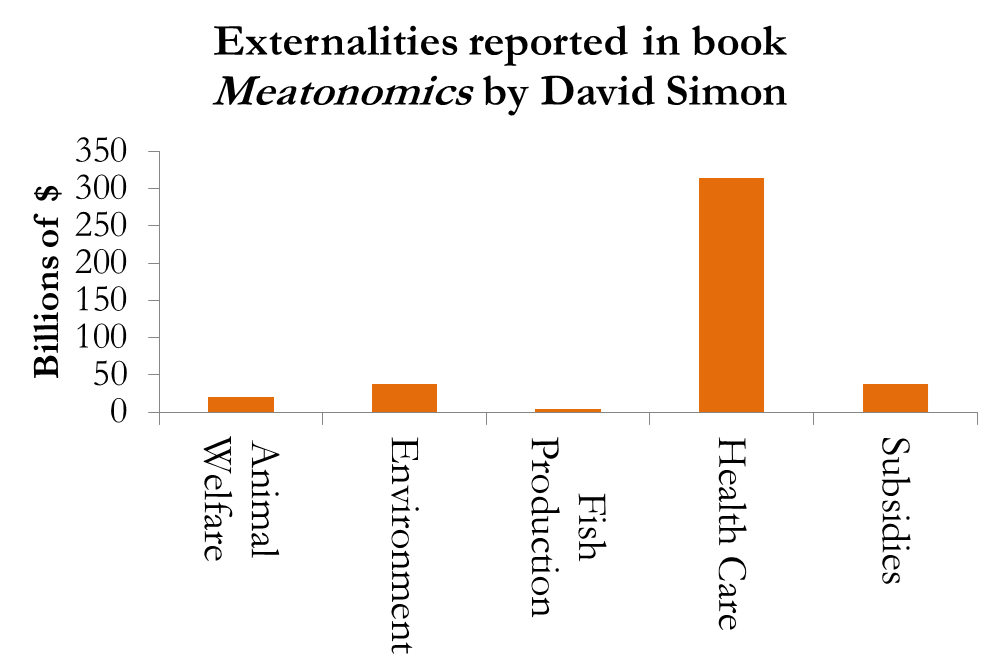

David Simon is a vocal critic of meat, dairy, and eggs (hereafter, meat), and when he attacked the meat industry in his book Meatonomics he did so in the using the concept of externalities.

Quotation 2—Food activist David Simon on the price of meat

Factory farmers keep prices low by dumping over $400 billion dollars of production costs on society each year. That means a $5 Big Mac really costs $13.

—Meatonomics: The Bizarre Economics of Meat and Dairy [video promotion for the book Meatonomics]. Accessed July 21, 2014 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qgdbfrgMjoY.

Simon goes so far as to attempt to estimate these externalities for meat consumption, and his results are shown below. Let me be clear: I am not endorsing these estimates. Nor should anyone interpret them to be externalities estimated by economists. Instead they represent a food author’s attempt to measure all externalities based on his reading of the scientific literature. I report them so that the student can better understand agricultural controversies. To understand controversies between vegans and meat-eaters one must understand the concept of externalities.

Figure 2—David Simon’s estimate of externalities resulting from meat, egg, and dairy consumption

The animal welfare externality

Externalities are not an easy thing to measure. Consider first the animal welfare externality represented by the first bar in Figure 2. This represents an externality of billions of dollars, but what do the numbers mean? I can tell you because they were based off my own research, where I gave people the opportunity to spend real money on different pork and egg products, using the unusual type of auctions described in the lecture Dairy products, surveys, and consumer experiments (part 2). I then observed their bidding patterns. I found that consumers would spend considerable amounts of money for products that provided a higher level of animal welfare.

They will not only spend more money for the food they themselves consume, but will pay money to improve the welfare of animals consumed by other people. After all, if the suffering of a pig makes a person sad, does it really matter to the person who ate the animal? It matters some, I am sure, but some people value kindness to animals regardless of whether they themselves eat the animal.

This empathy for livestock expressed by the subjects gives us insights into the angst some people experience knowing that animals are raised in cramped cages, as in the pork and egg industry. This angst can be expressed in dollar terms, and that is where the billion-dollar animal welfare externality in Figure 2 comes from.

Yet, if you ask me—the person who did the research—I would say that the externalities are an over-estimate. This is because people behave differently when they are observed by researchers. In auctions where people know they are being observed, they tend to place more emphasis on ethics than they do in the grocery store. We know this because in my experimental auctions a majority of people were willing to pay higher prices for cage-free eggs and crate-free pork, but in the grocery store cage-free eggs are only about 5% of all egg sales (and that includes organic as cage-free) and crate-free pork is almost impossible to find. People are so sensitive to being watched that they are more likely to donate money to a charity if they are in a room with a picture of two eyes mounted on the wall!(W1) Because most food purchases are made anonymously in a store, we cannot equate behavior in a laboratory setting to behavior outside the laboratory.

A second issue in dealing with this externality is that we are equating pollution with hurt feelings. Certainly, if a popular lake is polluted we consider that real damage that requires government action. But do you cause an externality when your eating of a burger offends the two PETA activists below? That is a much tougher call.

Figure 3—PETA activists

If we allow these hurt feelings to be considered an externality, then what is off-the-table? Perhaps you find loud music blaring from passing cards just as frustrating as PETA activists find the killing of birds for meat? You may say these are very different things, but what if most of the population disagrees?

For us to live together in a harmonious society we must tolerate the behavior of others that offends us, but at the same time, some behavior cannot be tolerated. Economists may have defined the concept of externality but they cannot tell us when to take them seriously and when they should be tolerated. Take smoking. Second-hand smoking seems like a real externality because it directly impairs the health of non-smokers. Yet many of us don’t even like to see people smoking. I personally do not like someone smoking when I am trying to eat, even if they are so far away that their smoke cannot harm me physically. Most people agree with me, and thus some places (like my university campus) ban smoking completely.

The point of this discussion is that even though the animal welfare externalities in Figure 2 were partially derived from my research, and my research was scientifically valid, there are legitimate reasons why it is overestimated.

The health care externality

The largest externality of Simon’s is that of health care, but this is also the most difficult externality to capture. Part of the externality assumes that when people purchase meat they are unaware of the health consequences. Assume for the moment that Simon is right and meat is bad for you. If people are not aware of this, then yes, people ignore these costs when they purchase meat.

The problem is that people already do associate meat consumption with adverse health outcomes. In one of my consumer surveys I found that people believe increasing their consumption of meat will increase heart disease, cancer, cholesterol, and food sickness—so even if these health hazards are not built into the price of meat at the grocery store, people take the health costs into account when they make meat purchases.

It is even possible that people overestimate the health externality from meat. From the 1970s through the 1990s saturated fats from animals (like those in meat and butter) became associated with high cholesterol and heart disease. People started eating less red meat and replacing animal fats with vegetables fats, like margarine. Now it seems that health experts are backing off this claim, and we are told to avoid products like margarine made with trans-fats. What has changed is our understanding of cholesterol and its link to health.(D3) Are consumers aware that saturated fats are not considered the health hazard it once was? Some certainly are, like those who read the June 2014 Time magazine cover story, titled “Eat Butter”.

Not everyone reads about health on a regular basis, though, and these individuals may believe meat and dairy products are less healthy than they really are, and so they may be overestimating the true health care externality. This would then suggest that these consumers should eat more saturated fats, not less. Note that I am not saying this is the case, but that it is a possibility, and these possibilities make externalities a complex topic.

Suppose we are considering the impact of meat consumption and obesity. If the American Heart Association(A1) is right when they say vegetarians have lower rates of obesity, and obesity impairs health, then the obese will require more expensive health care. Some claim the obese then increase the cost of health insurance for everyone, such that we are subsidizing health insurance for the obese, making this an externality.

Figure 4—Is this an externality?

However logical the argument may be, logic can run in the other direction. If the obese really do incur greater health care costs, then perhaps the cost of insurance rises for them but not others. After all, insurance companies go to great lengths to charge insurance premiums commensurate with expected costs. Or, if their health care is provided by their employer, perhaps the obese are paid lower wages to compensate for the greater health care costs their employer must pay? This would be discrimination, of course, but discrimination happens all the time. According to economist Timothy Taylor, this is indeed the case. Most of the health care costs of obesity are paid for by the obese, and not their slimmer counterparts.

Moreover (and this is somewhat morbid) the obese actually provide a positive externality to taxpayers because they die earlier, thus incurring fewer Medicare and Social Security costs than their non-obese counterparts.(T2) Would we want to encourage people to eat foods that make them obese because of this positive externality? Probably not. We don’t always want to discourage negative externalities or encourage positive externalities, because they might interfere with our ethical notions.

When to take externalities seriously

The point of this discussion is not to criticize the numbers in Figure 2, nor to make externalities seem like a useless concept. The concept of externalities is often essential for crafting effective governmental policy. Instead, what I am trying to convey is the difficulty of trying to measure some types of externalities, and the complexities of deciding whether they should be addressed by government policy.

Most of us agree that being close to a person with bad body-odor is unpleasant. It is also an externality. To correct for this, the city of Burien, Washington has made it illegal to smell bad. Who determines when a person’s odor is foul? Cops.(B1) Do we really want to give the police this authority?(B1)

But wait ... if we really dislike being around bad-smelling people, are they not paying the cost of their poor hygiene? If a smelly person applies for a job they are qualified for but does not get the offer simply because of their smell, that individual paid a very high cost. Just because the cost of an externality is not reflected in one market price does not mean it is not reflected in some other market price, or that the cost does not occur in the social realm. The poor-smelling job candidate was not charged a dollar for each day he skipped a shower, but he did pay a cost in terms of lower wages and/or social ostracism.

Even if he did not pay a cost for his poor smell, for many people the idea of making bad body odor illegal just seems too outrageous.

There are cases where taking an externality seriously is rarely controversial. In cases where agricultural activity results in water pollution, few would argue that government has no role in preventing this negative externality. Most large surface waters of the U.S. are regulated by federal, state, or both levels of government.

Figure 5—Eutrophication of water, a serious externality

How to confront negative externalities

In those cases where we know we need government action, what is the best way to discourage the negative externality? This lecture will discuss three methods of correcting for a negative externality, and will use the example of water pollution stemming from agriculture as an example.

Command-and-control

Consider command-and-control. When farmers apply broiler manure in Oklahoma there are very specific regulations on how this should be done. The Oklahoma government commands and it controls. Broiler producers and anyone applying broiler manure must obtain a license and attend educational classes to learn how to handle the manure responsibly. They are told to take soil test samples to see how much phosphorus is in the soil, and then how to use this information to determine exactly how much manure they can apply to each acre of a crop.(O1)

Command-and-control is restrictive in that it gives farmers little opportunity to devise better ways of achieving the same reduction of externalities. Although it can be an inflexible policy tool, sometimes such inflexible rules are the only reasonable option.

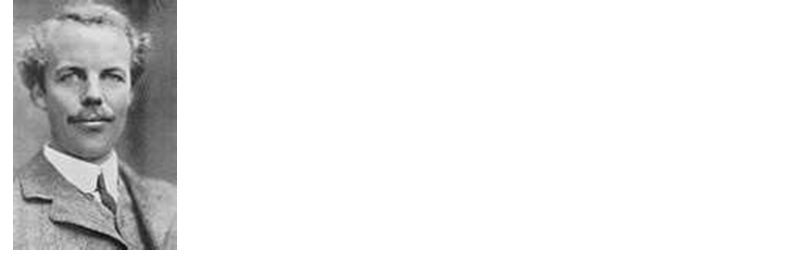

Pigouvian taxes

Pigouvian taxes are named after the economist Arthur Pigou, who advocated charging firms a tax for each unit of externality they generate. After all, if a negative externality is simply a cost not reflected in the good’s price, a simple fix is to tax the externality. Once firms have to pay the tax they will raise their prices, and once the externality cost is reflected in the good’s price it is no longer an externality.

Figure 6—Economist Arthur Pigou (1877 - 1959)

This is the tool Sweden employed to reduce fertilizer runoff. After taxing fertilizer purchases they found that fertilizer declined by 15-20%. With fertilizer being more expensive farmers presumably went to greater lengths to use it more efficiently, and if they did so, then fertilizer runoff may have been reduced with only modest impacts on food production.(N1)

Cap-and-trade

Cap-and-trade is the most interesting of the three tools. Those who have kept abreast of the climate change debate in the U.S. might remember that when the Democrats came to power in 2008 many thought they would implement a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions. The idea is simple. There is a certain amount of carbon being emitted. We know we can’t reduce emissions to zero, but they must be reduced by some amount. Let’s say we want total emissions to be X = (0.7)(current emissions in tons). This reduces total emissions by 30%. This can be achieved by forcing all large emitters of carbon to purchase a permit for each ton of carbon they are responsible for. The government then limits the number of permits so that no more than X tons can be emitted. For instance, they might give permits for free to each large emitter, but the number of permits allows them to emit only 70% of their previous amount. That’s the “cap” part of cap-and-trade.

We don’t just want to reduce our emissions. We want to achieve this reduction at the least possible cost. Put differently, we want to reduce pollution but to give up as few toys as possible. This can be achieved by allowing people to buy and sell these permits to one another, at any price they negotiate. That is the “trade” part of cap-and-trade. By allowing the private sector the opportunity to trade permits, the government is letting it decide how these emissions will be met, and by doing so, achieve the reduction with minimal impact on economic output.

The beauty of the cap-and-trade system is that it encourages people to find innovative ways of reducing their emissions. To see this, suppose a cap-and-trade system is established for reducing nutrient runoff into a river. Nutrients come from multiple sources, including wastewater treatment plants, chemical fertilizer applications, and livestock manure applications. Suppose that a wastewater treatment plant is faced with a dilemma. More wastewater must be handled. It must either buy another permit so that it can discharge more nutrients into the river, or it must spend $5,000 to treat the water more thoroughly.

Then suppose there is a farmer who raises hay. The chemical fertilizer she applies to the hay field will result in some fertilizer runoff, and some nutrients entering the river. She has a permit allowing this pollution, but she has another option. She can eliminate the need of her permit by installing a filter strip around her field. This filter strip is simply a strip of unfertilized grass on the border of the hay field, which captures fertilizer runoff before it can enter the river. This filter strip only costs the farmer $3,000 to install.

The plant and the farmer can strike a mutually-beneficial deal. If the farmer sells her permit to the treatment plant for $4,000 she makes $1,000 in profit. If the plant buys the permit for $4,000 it saves $1,000. The exchange benefits both the farmer and the plant by $1,000 each. The ability to trade permits lowers the cost of production for the entire private sector, relative to a scenario where each firm had to reduce its externality by the same percentage. By reducing the cost of complying with regulations, the cap-and-trade system allows us to achieve the same pollution reduction while giving up the fewest toys. Cap-and-trade allows us to pollute the same amount at a lower cost, or spend the same amount of money to produce less. The amount of savings generated by cap-and-trade depends on the setting and how well the policy is designed. Savings could be as low as 2% reduction in costs, or as high as a 60% cost reduction.(D4)

Some people are uncomfortable with cap-and-trade because giving permits for people to pollute seems like it condones pollution. That is not the case. Remember that pollution is capped at a lower level than before, reducing pollution. Moreover, that cap can be reduced over time as the private sector creates more efficient ways of reducing pollution. Also, recognize that some pollution will result from Pigouvian taxes and command-and-control. It is impossible to raise crops and livestock without some water pollution.

This is basically the system that was established in 2010 to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. The program is officially referred to as a TMDL program, standing for “Total Maximum Daily Load”. The EPA establishes the maximum amount of pollutants that enters the bay each day. This maximum amount is the “cap” on pollution. The cap is set below the old level of pollution and is reduced over time, with the goal that by 2017 it will reduce pollution by 60%.(C2).

Figure 7—The Chesapeake Bay

Within the TMDL program is what the EPA refers to as water quality trading—equivalent to the trading of pollutant permits described above. An emitter can increase the amount they pollute, and a new source of pollution can be established, so long as they pay some other source to reduce their pollution by the same amount. This is exactly what happened when the wastewater treatment plant in the example above was able to pollute more by buying the permit from the farmer.

Government failure

The presence of externalities is often referred to as a market failure. For example, the market for broilers failed to account for pollution costs in the price of chicken. Often the existence of market failure is seen as sufficient justification for government intervention, but we must remember that governments can fail also.

In both the private sector and the government, individuals may try to seek personal advantages at the expense of others. The broiler industry seeks to reduce poultry prices by not paying for the water pollution it creates, and politicians seek to deliver benefits for themselves, their constituents, and their donors by imposing costs on the citizenry at-large.

Consider the example of corn ethanol, where corn is raised and processed into a fuel that is added into gasoline. It was initially seen by some as an environmentally-friendly and renewable source of energy. This gave politicians the consent to subsidize ethanol production and require a certain amount of ethanol to be blended into gasoline. Ethanol producers and corn farmers benefitted handsomely, but it soon proved a failure to everyone else. Environmentalists no longer support the program.

Quotation 3—Environmentalists hate corn ethanol

Politicians are high on turning corn into fuel—but ethanol not only hurts the environment, it’s also one of America’s biggest political boondoggles.

—Goodell, Jeff. March 23, 2011. “The Ethanol Scam”. Rolling Stone.

One should not view corn ethanol as an honest mistake made by politicians. Politicians exploited misperceptions about corn ethanol to deliver benefits to individuals that would support their political aspirations. One should never assume that legislation passed ostensibly for the social good is actually intended for the social good, and even if it is, one should never assume that good intentions lead to good outcomes.

Quotation 4—Al Gore on why he supported corn ethanol

One of the reasons I made that mistake is that I paid particular attention to the farmers in my home state of Tennessee and I had a certain fondness for the farmers in the state of Iowa because I was about to run for President

—Gore, Al. Quoted in: The Wall Street Journal. November 27-28, 2010. “Al Gore’s Ethanol Epiphany.” A16. (Note: the “mistake” was supporting corn ethanol subsidies).

So when we attempt to manage externalities through government intervention in markets, we must be diligent in holding politicians and government agencies responsible for their performance. The only way to control politicians is by influencing large sections of voters and / or spending large amounts of money on lobbyists. If you look back on the last four decades, this is something environmental groups have learned to do well. Remember, though, that our goal should not be to reduce pollution to its lowest possible level, but to reduce pollution significantly without crippling our economy. This means that environmental groups, if they become too powerful, can do more harm than good.

It is your charge, as a citizen in a representative democracy, to do your part to empower environmental groups when they need it, but to restrain them when they become too powerful.

Figures

(1) Original figure. Source: Economic Research Service. 2014. Food Expenditures [database]. United States Department of Agriculture.

(2) Original figure. Source: Simon, David. 2013. Meatonomics. Conari Press: Newburyport, MA.

(3) By https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Postdlf [GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons.

(4) By Herecomesdoc (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

(5) By Kmusser [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

(6) In public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A.C._Pigou.jpg.

(7) By Kmusser [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.