You are what you eat: American roots of food culture

An American entitlement to meat

If one thing distinguishes American culture, it is the dominance of meat, what historian Maureen Ogle refers to as a sense of entitlement to meat.(O1) The abundance of land in America meant that raising meat was cheap. During the Revolutionary War, American soldiers were taller than British soldiers, and during this time period Americans were, according to a French traveler, eating eight times as much meat as bread. Vegetables were probably not considered essential for a complete meal, and were often seen as a garnish, a flavoring, or medicine.(C1) For many early colonists pork was almost free, as they could simply let hogs loose in the surrounding woods and venture out once or twice a year to gather or hunt them.(A2,L2)

Americans really did feel entitled to decent meat. When a young lady of obviously low income in the 19th century purchased a tenderloin from a Boston meat seller, he suggested she could save money by purchasing the round steak instead. Who knows if the remark was made in kindness, but that was not how it was taken, as she replied, "Do you suppose because I don't come here in my carriage I don't want just as good meat as rich folks have?" (page 50).(O1) Affordable meat created some semblance of equality within America, and a sense of national identity.

Meat eaters rule the vegetarians

Americans became increasingly proud of their country's rise as a Republic-empire, and as they saw America's European siblings extend their empires as well, they couldn't help noticing that the people who devoured meat seemed to easily conquer those who didn't. Meat then became not only a source of personal strength, but of American exceptionalism. This idea is still alive today. Drive through the state of Nebraska, and chances are you will see at least one bumper sticker that says, "The West wasn't won on salad!" The idea is that America is strong—a carnivore, like a hawk or lion. Regions with vegetarian diets are then implied to be weak—herbivores, prey, certain to be dominated by others.(O1)

Figure 1—Bumper sticker you might see in Nebraska

This belief was held even by those countries conquered by meat-eating Europeans. Mahatma Gandhi, as a young man at a time when India was a British colony, noticed how the British were taller and stronger than his fellow Indians, and he naturally assumed the difference was due to Indian vegetarianism.(G2) Obviously, Gandhi didn't know that the Roman Empire was established by a bread-eating army. The small portions of meat consumed by centurions did not seem to hinder Rome's ability to defeat the meat-eating Germans. Who knows how much meat Caesar ate, but his soldiers didn't eat much, and they did all the fighting.

We are a weak people because we do not eat meat. The English are able to rule over us, because they are meat-eaters.

—Answer by a friend to Gandhi's question of why some of their teachers were secretly consuming meat.(G2)

The flexibility of food culture

If this discussion, and the content in part 1 of this lecture, do not seem to have a precise point, that is the point; when it comes to the role of food in human society, anything is possible. Although the nourishment humans require from foods has remained virtually the same for thousands of years, foods' role in human culture varies across space and time. The cultural component of food evolves out of cultural values and the challenges confronting a society.

Let's consider the flexibility of food culture by briefly visiting two controversial issues today: farm animal welfare and global warming.

Figure 2—A turkey lives to see another day

Consider this observation. In a land where a large majority of people eat meat, American presidents now pardon a turkey every year at Thanksgiving. They do this, and then eat meat from a non-pardoned turkey for their Thanksgiving meal. Why eat meat but then suggest in a ritual that we should not? What this represents is an acknowledgement that animal emotions matter. Three decades ago animal welfare was a non-issue. Only the extremists like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) members asked whether hogs raised for meat were treated humanely, and for the ordinary American, being called an animal rights activist was as bad as being called a communist. Now, animal advocacy groups are much larger, and have the sympathy of ordinary Americans. Livestock industries have also evolved to care more about animal treatment. When new undercover videos expose animal cruelty on farms, both animal advocacy groups and livestock industries express shock and disgust.

To what extent does the ordinary American care about animal welfare? My research suggests around one-third of the people don't care about the well-being of farm animals, but around two-thirds believe that, while society has no obligations to make sure animals are happy and content, society should ensure that farm animals do not suffer—only 1% of people think that farm animals are entitled to a happy and content life.

While many consumers would rather not know how their food is produced, fearful they will not like what they see, others insist on transparency in agriculture. They believe the consumer has the right to know how the farm animal is treated. Enough people have this belief that the skit comedy show Portlandia performed a farce of an animal-loving couple entering a restaurant, wanting to know the name of the chicken they were about to eat and whether it "paled around" with other hens.

Video 1—Scene from Portlandia(P1)

Note: this video can be used under Fair Use laws because it is used for illustration purposes to reinforce understanding of a topic, it is clearly related to the teaching goals, is not done just for entertainment value, the excerpt is no longer than necessary, the source of the video is clear, and the video is only available to current students enrolled in Dr. Norwood's class. Moreover, the video is available on

http://CriticalCommons.org at

this link.

Most people believe hens suffer in the battery-cage egg production system. California voters choose to ban cage egg production in 2008, and in surveys and experiments Americans consistently express displeasure at battery-cages. Despite this, although cage-free eggs are available in most stores, they constitute only 5% of all egg sales (and that’s including organic). Why do consumers express one attitude towards cage egg production in the voting booth and surveys, and then express the opposite attitude in the grocery store?

Figure 3—Battery cage egg system

It might have to do with price. The higher price of cage-free eggs may be more apparent in the grocery store than the voting booth. It might have to do with ignorance. Some consumers actually think they are buying cage-free eggs at the store when they are not. They might mistakenly assume brown eggs are cage-free eggs. Much of this discrepancy just seems part of human behavior. Economists say that people act more like a “citizen” in the voting booth and surveys, but like a “consumer” in the grocery store. This means that in the former they are placing more emphasis on ethics, and in the latter they are trying to get a good deal.

Figure 4—Cage-free (aviary) egg system

This must frustrate egg producers. Consumers tell them to produce cage-free eggs but buy very few of them. This is unfortunate, but is the natural course of an evolving food culture placing greater emphasis on ethics. There are three pieces of good news, though. One is that, as California voters proved, our evolving ethical notions can be manifested in the laws we pass—an example of democracy at work. The second good news is that markets also respond to changing food preferences—an example of capitalism at work. I assure you, the second consumers consistently pay more for cage-free eggs at the store, egg producers will eagerly erect new cage-free facilities to profit from the demand.

The third piece of good news is that all of this demonstrates that consumers don’t just care about themselves—for many, even the feelings of a simple little hen matters. That says much about the character of the American consumer. However, consumers should not just assume that products which seem animal-friendly actually benefit the birds. Cage-free egg production has many advantages for the birds, but some disadvantages, such as a higher mortality rate. Chickens can only remember a pecking order of around thirty birds, so when they are let loose in an open barn with thousands of birds they continually fight in their effort to establish a pecking order.

A similar problem can be found in free-range systems, like the one below. Birds are given outdoor access for most of the day, which provides most of birds’ needs while also limiting aggression. This also leaves them vulnerable to predators. I have been on a free-range egg farm where mortality rates were as high as 25%, largely due to hawk attacks. Compare that to the mortality rate of 3% in cage egg systems, and 7-10% in cage-free systems.

Figure 5—Free-range system

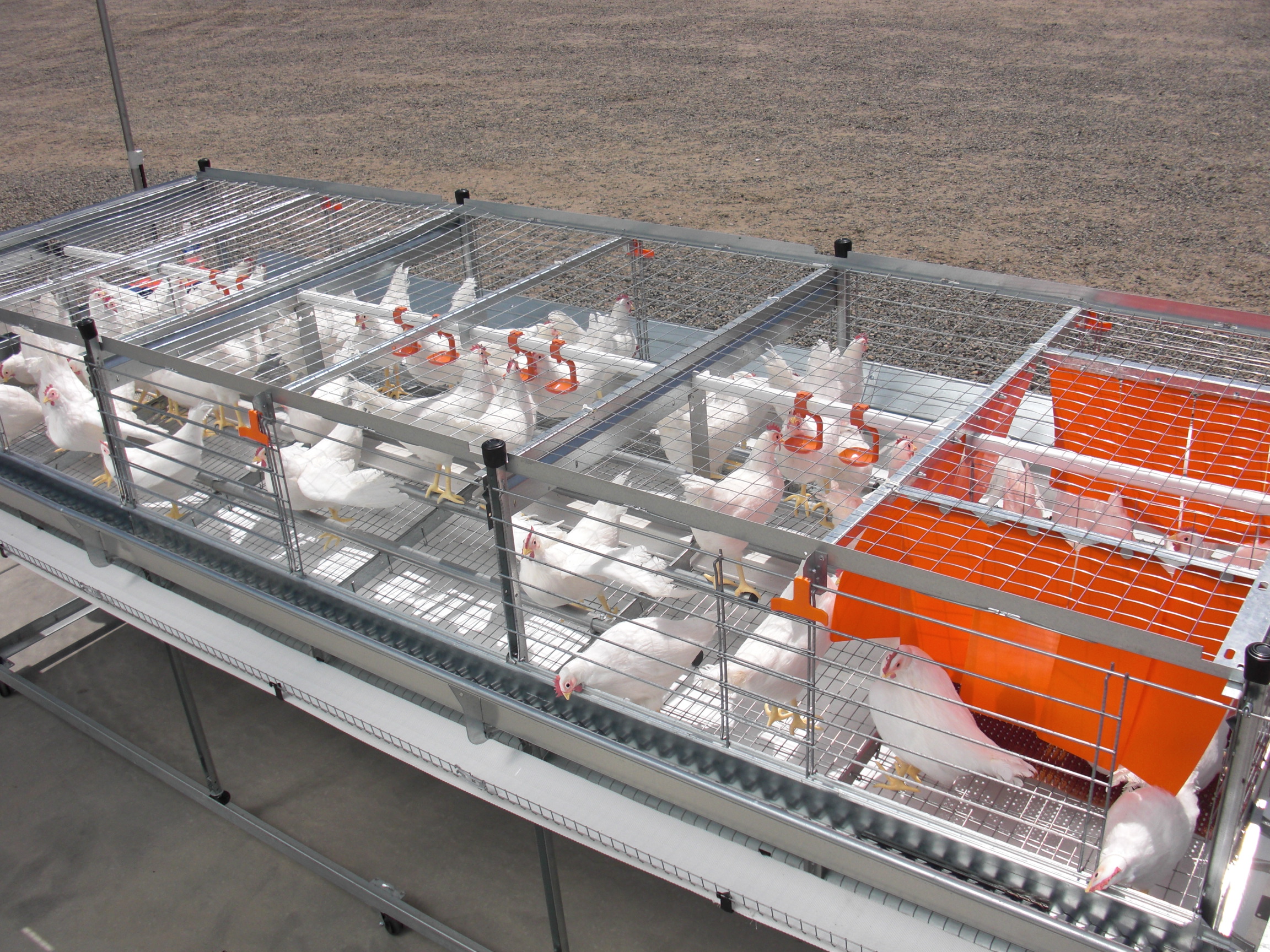

Most consumers may just assume that “cage-free” is better for the birds, and be oblivious to the high mortality rates. Fortunately, it is the egg producers who have stepped in out of concern for the high mortality rates of cage-free and free-range systems. In an effort to assuage consumer concerns about cage egg production, while preventing high mortality rates, the enriched-cage egg production system has been developed. Although layers remain in a cage, they are given more room, in addition to perches, scratching areas, and nests for laying eggs. By keeping the birds in a cage, mortality rates remain low. Moreover, the enriched-cage system is more efficient than cage-free and free-range systems, and can thus keep egg prices low.

Figure 6—Enriched-cage system

Enriched-cages seem the best solution to providing high animal welfare while maintaining low egg prices. So ideal is this compromise that at one point the largest egg industry group (the United Egg Producers) and the largest animal advocacy group (the Humane Society of the United States) both agreed to encourage legislation banning cage egg production in the U.S., replacing it with enriched-cage production.

That joint effort is now abandoned. Why is that, given both the industry and animal advocacy groups supported it? Because other livestock groups opposed it. The chicken and pork industries in particular were concerned that such legislation would set a precedent for government interference in how livestock producers operate. What this means is that our food culture in terms of egg production cannot be separated from our food culture in regards to other foods.

Changing food cultures: the global warming debate

When it comes to food, our tastes are acquired partly from the food of our parents and grandparents, because that is what they fed us as children, and though old habits die hard, ethical views towards foods can change quickly. Consider how global warming went from a non-issue only two decades ago to a factor in determining how some people eat. As these words are being written, Al Gore announced he has become a vegan, ostensibly for environmental reasons. Though I do not necessarily believe the research fully supports this notion, meat, dairy, and eggs are thought by many to be associated with a large carbon footprint, and Meatless Monday is being adopted by organizations from elementary schools in the U.S. to the Norwegian military.

Although we are still debating how to best lower the carbon footprint of our food, we have already developed the ethical desire to do so, and that is also rather remarkable. It means that when we have figured out the relationship between certain foods and carbon emissions, we can achieve a smaller footprint quickly by altering our diets. And because we "feel good" from doing good, a feeling economists refer to as a "warm-glow", we might even obtain even more satisfaction from our food.

Food and identity

So we say, "You are what you eat." Well, then, we should first decide what kind of identity we wish to project, and then choose the foods that accomplish that. Our foods must reflect not only our tastes, but our values. This decision involves looking at the political side of food, and politics can be uncomfortable, I know. But you are able to speak out on political issues because you have political rights, and those rights are envied by most of the rest of the world.

Stephen Colbert recently poked fun at the American diet by remarking ...

As we all know, you are what you eat. And I’m proud to say Americans are the tastiest,

crispiest, saltiest, most thoroughly processed corn-based people on Earth. Plus, we come in enormous

portions, and our packaging is bright and cheery.

—Comedian Stephan Colbert in America Again. Grand Central Publications: NY, NY.

Although it is indeed funny, some readers may lament that it is partly true. They lament, because the quote makes them contemplate the eating habits they are passing on to their children. When jokes like these are made it conveys information about the consequences of a poor diet to a massive audience. Colbert is a huge celebrity, especially among the young and middle-aged. I must confess I have a poster of him in my office!

What is the best way to tell Americans that eating large portions of fast-food is dangerous? We can ask schools to hold programs on healthy diets, ban soda machines from schools, and place posters in the halls of high schools encouraging students to eat vegetables. This is how we confronted drugs, and how successful was the “just say no” campaign? Unsuccessful, you may say. Then ask, how influential are all the jokes made by all comedians about the unhealthy Western diet? More successful? Perhaps.

The point of this discussion is to observe that changes in food culture are not just the result of formal educational programs, but a product of the entertainment industry as well. Given how Hollywood has revolutionized how we view different sexual orientations, it could equally revolutionize how we eat, and that might not be a bad thing.

A food culture to admire

Let me end with a few words contrasting the food cultures of the developed world with their ancestors. Globalization has given us access to virtually every type of food, and this gives us greater versatility in achieving our goals. A typical American household has learned to cook food with influences from Asia, Latin America, Europe, and everywhere else. Many small towns even have a Chinese, a Mexican, and an Italian restaurant. Even though those foods have been modified to better suit American tastes, we have no problem eating a different culture's food because we no longer assume our culture, or our food, to be superior. This represents an openness to the world that must contribute to world peace. A food snob today will actually avoid traditional American dishes and seek the most novel and authentic food they can find. I'm talking about the kind of people who say things like, "You can't really find good Italian food in America...You know that this is not how Mexicans actually eat... You have to travel to Scotland to get a real Scotch Ale."

While we have embraced the world, we have not lost the culinary traditions of our ancestors. You can see this in the popular attempts to brew beer using Thomas Jefferson's recipe for pumpkin ale, and attempts to make traditional cider exactly as Thomas Jefferson did, even using the same variety of apples. An underground movement has been started to rediscover lard.

Let me give you a personal example. In historical South Carolina people would make sure they ate almost every part of a hog, including the head. A tradition emerged in the low country of cooking hash where you boil a hog's head for hours, then add things like potatoes, livers, and onions. Most people would find this recipe revolting, so while they still sell hash in the low-country, they substitute regular hog meat for the hog head. My family did not want to lose our traditions, so in our attempt to reconnect with the people and land from which we came, one Christmas we decided to make original hash, hog head and all, from a recipe that goes back...who knows how far.

Food used to be a marker of social class, where food was a part of inequality. Today this custom still exists, but at the same time we believe in a commendable level of food equality. Though some people struggle to find enough to eat, they don't starve. The poor can receive not only welfare from the government, but a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) card that allows them to buy a certain amount of food paid for by the government. This program used to be called food stamps, and the poor had to pay with stamps that were clearly different from cash or credit cards. This practice worked to stigmatize the poor at the cash register. The new SNAP card looks just like a credit card and allows the poor to acquire healthy food while preserving their dignity. Any child can eat a free breakfast and lunch at school, and to make sure this free food doesn't single-out children from poor families, some schools make sure the same foods are given to each student, whether they need it or not. These programs clearly show a culture that not only believes humans are entitled to good food, but also equality with others. This isn’t unheard of. Of the many constitutions during the French Revolution, one put in writing man's right to food. No, a right to food isn't unheard of, but it is rare. And I think that's rather beautiful. Yes, the rich eat better, but the poor don't starve—they are more likely to be obese! If Jean Valjean (from Les Miserables) were alive today he would not need to steal bread, but he would probably have to go on a diet.

Regardless of our religion, most of us now recognize that we are an animal that evolved out of nature, so we are a part of nature and have a responsibility not to destroy it. We take this responsibility seriously, which is why the environment and sustainability issues have become a concern for nearly everyone.

While we recognize that we are a part of nature, anyone who understands agriculture knows that it is anything but natural. Agriculture is the engineering of nature for our own benefit, so we must wisely engineer nature to provide inexpensive and healthy food while protecting nature at the same time. This isn't easy, and it requires us to be forward-thinking, altruistic, and flexible—three traits that abound in our modern food culture.

You are what you eat. Well, I believe the developed world contains the most compassionate, egalitarian, prosperous, and happy people to have ever existed. And these traits are manifested in the food we eat.

Related material

Update on egg production: The United Egg Producers and the Humane Society of the United States have abandoned their partnership to phase-out battery cages and replace them with enriched colony cages.

Figures

(1) Used with permission from the Nebraska Cattlemen Association

(2) In public domain at Wikimedia Commons (link)

(3 - 5) Used with permission from the United Egg Producers Association

(6) Personal photo.

References

(A1) Albala, Ken. Food: A Cultural Culinary History [lectures]. The Great Courses. The Teaching Company.

(A2) Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. 2004. Creatures of Empire. Oxford University Press: NY, NY.

(C1) Carroll, Abigail. 2013. Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal. Basic Books: NY, NY.

(D1) Durant, Will and Ariel Durant. 1963. The Story of Civilization. Part VIII: The Age of Louis XIV. Simon and Schuster: NY, NY.

(F1) Fisher, Edward. 2004. Peoples and Cultures of the World [lectures]. Lecture 13—Gatherers and Hunters. The Great Courses. The Teaching Company.

(F2) Fukuyama, Francis. 2011. The Origins of Political Order. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: NY, NY.

(G1) Genesis 2:7. New International Version.

(G2) Gandhi, Mohatma. 1957. Gandhi: An Autobiography. Beacon: Boston, MA.

(G3) Gupta, Sanjay. "If we are what we eat, Americans are corn and soy." CNNhealth.com Accessed December 5, 2013 at http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/diet.fitness/09/22/kd.gupta.column/

(H1) Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind. Pantheon Books: NY, NY. Page 13.

(L1) Lang, Jeanie. 1926. A Book of Myths. Library of Alexandria: Egypt.

(L2) Levenstein, Harvey A. 1999. Food: A Culinary History. "Chapter 39: The Perils of Abundance." Columbia University Press: NY, NY.

(L3) Lauden, Rachel. 2013. Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA (USA).

(M1) Montanari, Massimo. 1996. "Part Two—Classical World." Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present. Edited by Lawrence Kritzman. Columbia University Press: NY, NY.

(M2) Montanari, Massimo. 1996. "Chapter 15—Peasants, Warriors, and Priests." Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present. Edited by Lawrence Kritzman. Columbia University Press: NY, NY.

(N1) Norwood, F. Bailey and Jayson L. Lusk. 2011. Compassion, by the Pound. Oxford University Press: NY, NY.

(N2) Norwood, F. Bailey. 2011. "The Private Provision of Animal-Friendly Eggs and Pork." American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 94(2):509–514. DOI: 10.1093/ajae/aar073

(O1) Ogle, Maureen. 2013. In Meat We Trust. Houghton Miffllin Harcourt: NY, NY.

(O2) Obama, Barack. 2004. Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. Broadway Books: NY, NY.

(P1) Portlandia January 21, 2011. Season 1. Episode 1: Farm.

(P2) Personal communication with an anonymous American who traveled to Ethopia as part of a USDA group as a food safety expert.

(S1) Soler, Jean. 1996. "Chapter 4—Biblical Reasons: The Dietary Rules of Ancient Hebrews." Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present. Edited by Lawrence Kritzman. Columbia University Press: NY, NY.

(S2) Standage, Tom. 2009. The Edible History of Humanity. Walker & Company: NY, NY.

(S3)Spar, Ira. 2009. "Epic of Creation (Mesopatamia)." Heibrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: NY, NY. Accessed November 30, 2013 at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hdepic/hd_epic.htm

(S4) Spencer, Colin. 2000. Vegetarianism: A History. Four Walls Eight Windows: NY, NY. Page 160.

(V1) Valdes, Didacus. 1579. Retorica Christiana. Accessed November 29, 2013 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Chain_of_Being_2.png

(Z1) Zuckerman, Catherine. August 2014. “Next.” National Geographic magazine.