Who feeds Stillwater?

Welcome to my town of Stillwater, OK, home of the Oklahoma State University Cowboys. If you include the college students, we have a population of about 45,000 people, and very few of them grow any of their own food. So who, then, feeds Stillwater?

Figure 1—Stillwater, OK welcomes you!

That is an awkward question, I know, one to which we all think we know the answer. No one person or organization is the sole authority for feeding the citizens of Stillwater. The residents earn money through some non-farming occupation, and then go to the store to purchase their food. However, there is more than one store. There are five grocery stores, a number of other smaller, specialty stores selling food, many restaurants, and for a small town a surprising number of food trucks. There is also a farmers market that is open twice a week, and the Oklahoma Food Cooperative that delivers locally produced food to the town.

I think the best answer as to who feeds Stillwater—and who feeds any modern democracy—is markets. There is a market for fresh, local food satisfied by the farmers market and the Oklahoma Food Cooperative. There is a market for convenient foods in great variety met by the grocery stores. There is a market for ready-to-eat foods met by the restaurants and food trucks.

Below is a picture of my favorite grocery store in town: Consumers IGA. Though this store may be my favorite, there are many other stores like it both in Stillwater and across the U.S. In the food aisles of this store you can see the success of modern agriculture. No other people on Earth has had access to food as delicious, as diverse, as convenient, and as affordable as the food in this store. If one is willing to purchase healthy food, no other people have found it so easy to eat healthy.

Figure 2—Consumers IGA Grocery Store in Stillwater, OK

This store provides a magnificent service: connecting the citizens of Stillwater with food produced around the world. There are peas grown in New Jersey, frozen immediately after harvest so that when defrosted it is like eating them right off the plant. Because of refrigeration we can eat fresh peas any time of the year! There are bananas grown in Guatemala, eggs from Indiana, pork from hogs that were likely raised in North Carolina, shrimp caught in Thailand, and bread from wheat that might have been harvested just down the road from Stillwater.

I say that markets feed Stillwater, because the manager of this grocery store did not need to call the banana producer in Guatemala to place an order of bananas. Nor did he talk to a pea producer in New Jersey, correspond via email with egg producers in Indiana, purchase shrimp directly from a boat in Thailand, nor did he even communicate directly with the business who produced bread from wheat grown in Oklahoma. The manager of this store can bring in food from any part of the world without ever leaving the town of Stillwater. For him, acquiring Thailand shrimp is just as easy as New Jersey peas.

If the grocery store manager had to acquire all of the food sold in the store directly from the farmer, there would be much less variety and most of the products would be priced higher. The only way this store manager can bring you food from around the world is if markets bring it to him, just like the only way a Thailand shrimp farmer can sell the shrimp she catches to you is if she sells it in a market. This is why we say markets feed Stillwater. If we instead remark that farmers feed Stillwater we would be ignoring a long line of markets and business people who played an essential, important role in providing you with a diverse assortment of high quality, affordable food. In fact, for every dollar you spend on food only about $0.16 goes to the farmer to compensate them for their contribution. The rest goes to food processors, wholesalers, retailers, and the like, suggesting that what happens to food after it leaves the farm is more important than what happens on the farm.

Figure 3—84% of the value of food is added after the farm

The manager bought the food from a wholesaler, that wholesaler bought those foods from other middlemen, and who knows how many other middlemen were required to bring bananas from Guatemala to Stillwater. For example, a Kansas City distributor helped bring the Thailand Shrimp to the U.S. Markets are not just a place where people buy and sell things. Markets are the collection of the millions of exchanges occurring between the people who produce raw materials, the people who transform those materials into a consumer product, and the people responsible for bringing those goods to a convenient location to sell directly to consumers. Markets are simply a series of trades, where food is property that changes hands from one person to another until it is finally eaten.

The benefit of trade: comparative advantage

Figure 4—Shipping by rail

The benefit of trade is obvious in my favorite grocery store. Stillwater could produce its own bananas, but we would have to do so in expensive greenhouses. That would be a ridiculous thing to do, seeing that we can import bananas from Costa Rica for such a low price. Likewise, Oklahoma is particularly suited to wheat production, and much of what we produce is exported to the world. Certainly, some of that wheat is consumed in Guatemala. When each region produces the foods it is best suited to produce, and then trades some of it for the goods it cannot produce well, everyone has more food. As you know, a team performs best when each member performs the tasks best suited for them, and the same goes for the world in food production.

The benefit of trade: specialization

Even if all the regions of the world had the exact same soil, climate, and resources, making each region equally suited for the production of any good, they can still benefit by trading with one another. When a farm—or any business, for that matter—is able to specialize in one or a few goods they are able to hone their skills and purchase expensive machinery that boosts the productivity of labor. A small, diversified farmer with 50 acres of wheat and 30 cows could never afford combines and expensive feeding equipment. Instead, some people specialize in wheat production and produce a lot of it with combines, and others manage large feedlots where they feed thousands of head of cattle.

Trade encourages specialization because it gives any one business a larger potential base of customers. Kansas farmers would never raise as much wheat as it currently does if it could only sell wheat to other Kansans. It is because it can sell wheat around the world that it can produce enormous amounts of it with huge tractors and expensive, scientifically developed wheat seed.

Figure 5—Combine harvesting wheat

Figure 6—Machinery used to feed cattle at a feedlot

The U.S. produces far more wheat than they consume, and it is because of their large output that they can produce wheat at such a low price. We are able to do this because the wheat we do not consume is easily exported to other countries, so without trade, there is less specialization, less technological innovation and development, and less food.

There is considerable specialization not only in what foods are produced, but one’s specific role in the production of that good. For a can of spinach, there are some businesses that specialize in producing the spinach, some in producing the aluminum can, and some in producing the can’s label. For a whole chicken, some specialize in producing the chicken, some in the corn the chicken eats, some in the plastic packaging in which the chicken is sold, and some in the refrigeration used to keep chicken from spoiling as it is transported. In a modern, prosperous country, everywhere you look you see specialization and trade, even in the ancient industry of food.

In fact, trade is what allows citizens of the modern world to accumulate so much wealth. To illustrate, suppose that you are Robinson Crusoe, alone on an island, and everything you consume you have to produce yourself. Even if you know how to produce everything from grilled fish to pharmaceuticals, the fact that you have to spend so little of your time devoted to each good means that you will never become adept at producing any one good. There isn’t enough time to polish your skills, research new production technologies, or build machinery and tools that improve your productivity.

Though humans are the most intelligent of animals, we only prosper in groups. Alone on an island we stand less chance of survival than a bird, or even a dumb crab. Each of you will go out into the world and specialize in a particular job, and will use the money you earn to buy goods produced by other people. Imagine how long it would take you to personally produce all the goods you consume in a day. One lifetime is not enough. We are prosperous because we specialize and trade, but this is no recent insight of my invention. It was best said by the French economist Bastiat in the nineteenth century.

Figure 7—Frédéric Bastiat, a 19th Century French Economist and Journalist

Bastiat pic.jpg)

Quotation 1—From the 1850 book Economic Harmonies

It is impossible not to be struck with the measureless disproportion between the enjoyments which this man derives from society and what he could obtain by his own unassisted exertions. I venture to say that in a single day he consumes more than he could himself produce in ten centuries.

—Bastiat, Frédéric. 1850. Economic Harmonies. 1: Natural and Artificial Organization.

Read a longer version here

Technology and trade

If you ask most people why food is so cheap today they are likely to remark on the technological innovations in agriculture, and they would be correct, but they are likely to neglect to add that those innovations are made possible through markets.

Most technologies tend to be useful only to larger farmers. The automatic milking machines used on today’s dairies greatly improves the productivity of labor, but is unprofitable on farms with just a few cows. Driverless tractors are a blessing for farmers with thousands of acres, but they are too expensive to use on a fifty acre farm. As we have seen, large farms and thus better technologies are only desirable if regions can trade with one another.

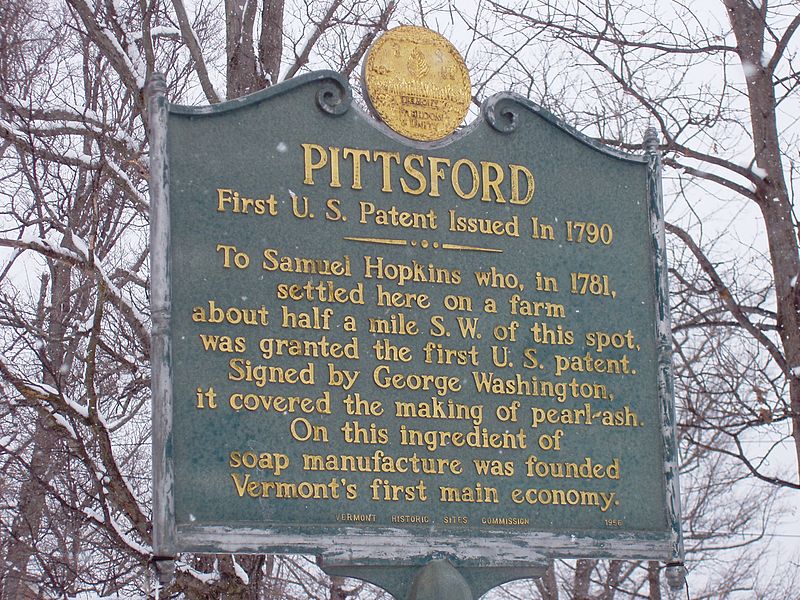

Technology does not fall from the sky like manna from heaven. Most of the time they are the deliberate attempt of an entrepreneur to make money. That is why governments award entrepreneurs who create new technologies with patents, giving them a monopoly in the sale of that technology for a number of years. Indeed, the first U.S. patent was awarded to Samuel Hopkins in 1790 for his new way of acquiring potash from the ashes of burnt plants.(P1)

Figure 8—Patent for potassium fertilizer innovation

Skepticism of technology

There is no doubt that trade and technology have reduced the price of food, but some wonder whether the low price hides costs that society pays elsewhere. If low food prices come at the expense of poor future health, soil erosion, and pollution, then the total costs of food may be higher today than decades prior. Those who believe the low food prices in my favorite Stillwater store have hidden costs sometimes turn their back on the modern technologies used to grow food and the modern food distribution system that brought Thailand shrimp to Stillwater, OK.

These individuals may then seek organic food. If certified organic, the farm never used synthetic pesticides or chemical fertilizers, two modern inputs used to produce the vast majority of food but are nevertheless viewed skeptically by some. Other individuals do not even want organic food if it is sold in a standard grocery store like Walmart, because they fear the low prices from distant regions must be masking a hidden cost. Such individuals often seek food at farmers markets, where they can meet the farmer and know there no large food corporation who handled the food between the farmer and the consumer—some people fear corporations particularly. Certainly, Stillwater acquires very little of its food from farmers markets, but those who do shop there particularly value its food.

So, who feeds Stillwater? I’ll say it again: markets. This food market includes conventional grocery stores like Walmart and Consumers IGA, but farmers markets as well. The manner in which farmers raise foods depends on the extent of each market. The market for conventional groceries is huge, and so most of agriculture uses advanced technologies that only large farms can afford, but as the farmers market grows it might cause more food to be produced on smaller farms, using more traditional techniques. The question of who feeds Stillwater is then being decided every day by how each of us shop, as well as the social culture and government policies that alter our shopping behavior.

This means that to “understand modern agriculture” we must understand the large farms that supply the grocery store, but also the small farmer selling locally.

Figures

(1) ((By Fletcherspears (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons)

(2) Used with permission from owner/manager of store

(3) Canning, Patrick. February 2011. A Revised and Expanded Food Dollar Series. Economic Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Report Number 114.

(4) By Doug Wertman from Rogers, AR, USA (Cajon Intermodal) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

(5) By Cyron (flickr.com) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

(6) Personal photo.

(7) Wikimedia Commons

(8) CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/), GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons)

Note: The video part of the lecture contains some original videos and some from the Sunup show.