Local foods and panoramic-blurriness

A major motivator for shopping at farmers markets is the belief that locally grown food will taste better and be more nutritious. It is also clear, however, that people are also drawn to local food in the belief that it is more ethical. The low prices are grocery stores can make some suspicious that the prices are low because they do not account for some of the social costs involved in agriculture, like soil erosion that threatens future generations’ ability to feed themselves, pesticide use which can potentially harm human health and the environment, water pollution from the use of chemical fertilizers, emissions of greenhouse gases, and the welfare of livestock raised for food. It isn’t necessarily the case that these beliefs are true, but it is admirable that consumers want their food to be ethical, and are willing pay more for it.

Understanding how local food effects you personally is rather easy. Only a couple of trips to the farmers market is needed to learn how different food tastes. Researching the relationship between food and health is not easy, but identifying the foods that best matches your taste profile and health goals is possible.

Identifying what is an ethical food—one that affects society positively—is far more difficult. It requires you to perceive the difference between how local and non-local farms operate, and how those differences translate into changes in the environment, children, the poor, farm animals, and the future. If a farmer down the road is using the same chemical nitrogen fertilizer as the one from an unidentified state, how would we know whether the local farmer’s nitrogen application leads to less pollution? How many of us know the carbon emissions per pound of beef produced from cattle in a feedlot versus grass-fed cattle? Which farm leads to less soil erosion: the soybean farmer who uses genetically modified soybeans and does not plow the soil, or the organic soybean farmer who does plow the soil? Which hogs are happier, those kept on a barren, concrete floor in an individual stall with insufficient room to turn around? Or the hog on that same concrete floor with slightly more room, but sharing that space with other hogs who are often cruel to one another?

The point is that understanding the link between food and our tastes and health is possible. The picture of tasty, nutritious food is clear, sharp, and crisp. But when we try and gain a panoramic depiction of how agriculture impacts everything from the environment to the poor to farm animals, the picture becomes blurry. Though we want ethical food, identifying the most ethical food can be harder than finding a vegan restaurant in a small Texas town!

It is like a road map. Look closely and you can clearly see the roads connecting one town to the next, but only those two towns. To gain a bigger picture of how the roads intersect with one another, connecting any one town with any other, we must zoom out, moving further back from the map. The further away from the map the more we can see of the entire map but the less we can see of the roads. Sometimes, to see the whole map at once makes for a blurry picture, and we lose sight of the roads connecting any one town to its next closest.

Sometimes, when you try and obtain a better focus on the world by studying the “big picture” more intensely, some of the ethical notions about how food and society interact turn out to be wrong, or more nuanced than initially thought. Take, for instance, the role between local foods, the local economy, and the carbon footprint of food.

Challenging intuition: Locavores and the local-economic stimulus

If you asked economists the best way to wreck an economy quickly, they are likely to answer: erecting trade barriers with other regions. This is true regardless of whether we are talking about a nation’s economy or that of a small town. If this is the case, why do locavores argue that spending on local foods stimulates the local economy and increases the population’s wealth?

I admit, the idea of helping the local economy by buying local products is intuitive. After all, you are directly giving your dollar to someone in your immediate region, instead of to a grocery store that transfers the dollar to corporate headquarters at who-knows-where. This is why people often say buying local foods (or local anything) “keeps the dollars local”. It is not clear to me, logically, why we should love our neighbor anymore than someone in another state (or another country), but intuitively I understand that emotion. So did Abraham Lincoln.

Quotation 1—Honest Abe on buying American

“I don’t know much about the tariff, but I do know if I buy a coat in America, I have a coat and America has the money—if I buy a coat in England, I have the coat and England has the money.”

—Lincoln, Abraham. Quoted in: Buchholz, Todd G. 1990. New Ideas From Dead Economists. Plume Publishing: NY, NY. Page 69.

Below is a quote taken from the documentary Locavore, an excellent film in many aspects but one that makes a poor economic argument. If Mr. English’s claim about the local food multiplier was correct, doesn’t that suggest we are fools to not pass laws prohibiting food imports?

Quotation 2—A locavore on buying local food

“... and another advantage of buying from your local farmer is ... economists call it the multiplier effect. And that’s the number of times a dollar circulates in the community before it leaves the community. So when I go to the grocery store, somewhere between ten and fifteen percent of my dollar stays in the local community—the rest leaves, because it has to pay the truckers, it has to pay the agribusiness giants and the ... warehouses. The money leaves the community. And if I spend the money with my local farmer, that guy, he pays his local property taxes, pays his school taxes (his kids go to the school), he goes and spends his money at the local feed store, the local hardware store—he spends the money here, in the community. It doesn’t leave the community. And, depending on who you talk with, that multiplier effect for agriculture—in an agricultural community—is five or six. That means it’s five times as effective as if you go to the supermarket and the money leaves the community. So [local food is] really economic development.”

—John English. 2012. Locavore: Local Diet, Healthy Planet. Documentary. Director: Jay Canode. Studio: Createspace.

On the day I talk about the local foods movement in my Introduction to Agricultural Economics I come dressed as the philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), who I believe is the first modern economist. Back in the eighteenth century Hume wrote an essay titled On the Balance of Trade where he proved that, over time, exports from a region must equal imports. If two million dollars are spent importing goods every year to Stillwater, OK, then two million dollars are earned in Stillwater, OK by exporting goods. This proof has never been refuted by anyone, and I have studied the proof myself and believe it sound.

Figure 1—Dr. Norwood as David Hume

The proof is quite simple. Imagine if Stillwater decided to export more than they import. More dollars would be coming into Stillwater than leaving, and if this continues indefinitely Stillwater would eventually accumulate all the money in the world. Obviously that can’t happen, and it won‘t, because as money accumulates in Stillwater it drives prices in Stillwater higher. These higher prices encourage Stillwater citizens to buy cheaper goods out-of-town, and when they do, imports rise until imports equal exports.

Conversely, if Stillwater tries to import more than it exports, more dollars will be leaving Stillwater than entering. Continued indefinitely this would deplete Stillwater of all its dollars, but that won’t happen because as dollars become scarce in Stillwater prices fall, and then Stillwater businesses seek to sell out-of-town at higher prices, and as they do exports will rise until they equal imports.(L1,H1)

No matter how you look at it, exports from a region must (on average) equal imports, so if Stillwater decides to replace some of its imports with local food, they are simultaneously deciding to decrease exports. This will benefit certain Stillwater farmers and harm certain Stillwater exporters, but overall will most likely reduce the town’s overall wealth.

Hume’s essay also has the interesting implication that you

also support your local community by increasing imports into the region by one dollar, because it will subsequently be matched by a dollar on local exports. Buy a German beer and you are indirectly buying something local as well.

Hume’ proof identified a few key concepts related to local foods (or local anything).

- Exports out of a region must equal imports into a region.

- This means that a region either trades with others or it doesn’t. If it tries to cut its imports to zero it would simultaneously reduce exports to zero, thereby secluding itself from the rest of the world.

- A dollar spent importing food comes back to your region in the form of exports.

- Thus, if imports increase by $1, exports will eventually rise by a dollar. You support your local economy by buying local food or imported food.

Given these assertions, it is rather frightening to hear the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack (in a response to a question about local foods) remark that, ideally, everything would be produced locally. Does Lockney, TX with a population of about 2,000 people really want to have to make its own computers and high definition TVs? It could not, and so what Vilsack describes as ideal is really destructive.

Quotation 3—A Secretary of Agriculture wants small towns to make their own iPads! :)

“In a perfect world, everything that was sold, everything that was purchased and consumed would be local, so the economy would receive the benefit of that ...”

—Vilsack, Tom, Secretary of Agriculture. The Washington Post. February 11, 2009. "Tom Vilsack, The New Face Of Agriculture." Accessed September 3, 2010 at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2009/02/10/ST2009021002624.html.

In the spring of 2014, I went to the Stillwater farmers market and interviewed a number of people about why they shopped there. One nice lady said the following.

Quotation 4—A farmers market customer on buying local

“The food is grown locally, and I believe [it is grown] in under more healthy conditions. And, I wanna support local ag[riculture].”

—Anonymous shopper responding to the question of why she shops at the Stillwater farmers market.

Though I am not saying this nice lady was wrong in her desire to support local agriculture,

but if she asked me what I thought of it I would say the following.

- Supporting local agriculture is not the same thing as supporting the local economy. Certainly, you may be helping a few specific farmers, but your actions are not likely to increase the overall wealth in you regional economy.

- Economists have considered the “keep the dollars local” argument illogical for centuries.

- In our panoramic blurriness, where we attempt to trace how our actions affect the whole world, our huge and complex social world, the big picture can become blurry and we can make mistakes.

- Is a farmer down the road more worthy than a farmer five states away? Certainly, I understand the impetus to favor someone you know over a stranger, but if we stop and think about it, why should we show more love to a person just because they are located closer to us? It isn’t an easy question to answer.

I know this argument is hard to digest if one hasn’t studied economics for years, so I don’t expect you to be fully convinced. What I do hope is that I made you second-guess your natural intuition that purchasing local food benefits the local economy. If so, I have demonstrated that we must always be skeptical of intuitive notions, however obvious they may seem at first. Aristotle once remarked that, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” I don’t expect to have fully convinced you that the locavore movement will not make everyone wealthier, but I do hope that you now see the value of questioning the idea, and that as you try to benefit the world by taking a panoramic view of how your food

eaffects others, your vision can sometimes be blurred without you being aware.

Challenging intuition: Is local food better for the environment?

Some people like to purchase local food because they want to do their part to preserve resources and protect the environment. They conclude that since local food did not have to travel as many miles (or food-miles, as locavores like to say) to reach the consumer it must use less fossil fuels, thus using less natural resources and resulting in a lower carbon footprint.

Quotation 5—Another farmers market customer on buying local

“I like the fact that [food at the farmers market] doesn’t use as much resources to get here. I just feel like I’m helping my neighbors and the environment by shopping here.”

—Anonymous shopper responding to the question of why she shops at the Stillwater farmers market.

The problem with the argument was panoramic-blurriness. Locavores tried to connect food with its impact on the world by taking into account the fossil fuels used to transport food, and the myriad ways fossil fuels affect the world, but the picture it painted was so blurred that locavores neglected to account for the amount of carbon emitted on a farm, and certainly, we care about total carbon emissions from our food, not just those involved with food transporation.

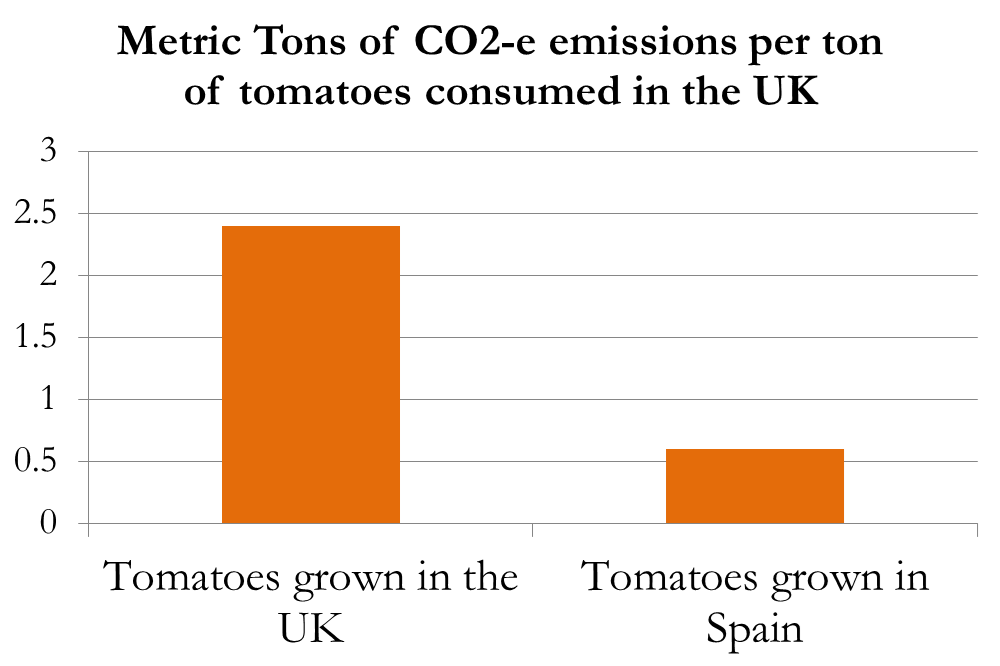

When food is produced and sold through markets, goods will tend to be grown in the locations best suited for the crop or animal. Tomatoes could be grown in the UK, using greenhouses, but they can be grown at a lower cost in Spain. Because Spain is warmer, they do not need to burn fossil fuels to warm the greenhouses. As a result, although UK tomatoes emit less carbon being transported from farm to consumer, emissions at the farm are far lower for Spanish tomatoes. In the end, accounting for the carbon emissions over all stages of tomato production, the footprint for Spanish tomatoes is only 0.6 metric tons per CO2-e per ton of tomatoes, much lower than UK’s footprint of 2.4.(B2)

So long as the quality of the tomatoes are comparable

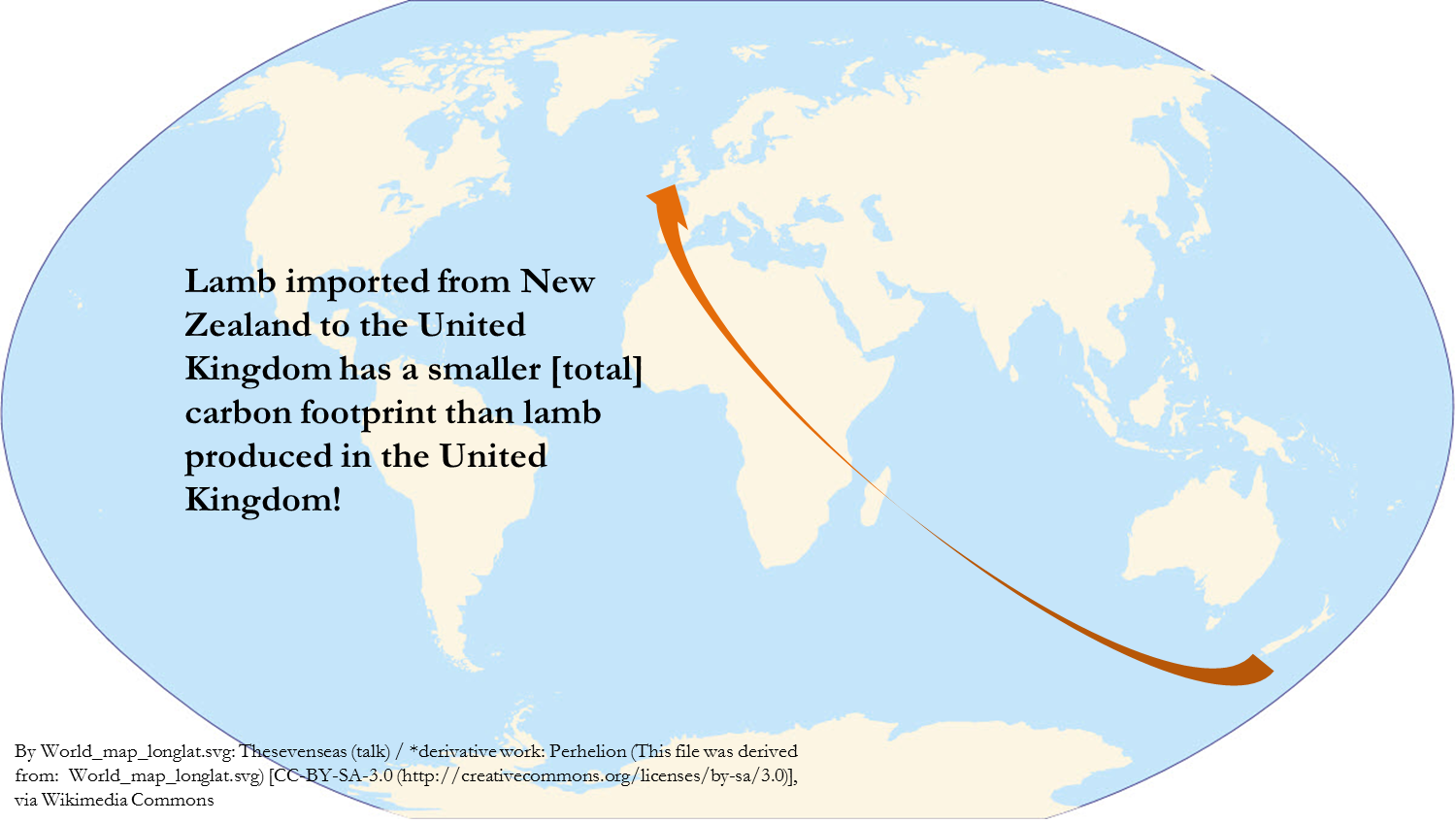

between, a UK citizen wanting a low carbon footprint should choose the tomato imported from Spain over the local tomato. Similar results have been found for other foods. Researchers have found that lamb sold in the UK has fewer carbon emissions if it is shipped from New Zealand rather than raised down the road.(S1)

Figure 2—Carbon footprint of tomatoes consumed in the United Kingdom

Figure 3—Distance matters little to carbon footprints

Moreover, even if food is transported many miles it is usually done so within an efficient transportation system, where Walmart’s lean distribution centers and trucks designed specifically to haul cargo can result in relatively little fossil fuels being used. Conversely, going a few miles out of one’s way in a minivan to buy a dozen eggs from a local farm is such an inefficient use of fossil fuels that it can make the carbon footprint of those eggs higher than buying them at a conventional grocery store. It might be better for markets to transport food from the farm to a local grocery store than for consumers to drive to the farm. (C1)

This is not to say that imported food always has a lower carbon footprint. Sometimes local food really is more environmentally-friendly. The point is that you cannot judge the relative carbon footprint of food based on how far the food was transported. When the locavore movement started taking off, many of its adherents believed they understood the relationship between how a food was produced and its carbon footprint. They believed the more local, the lower the carbon footprint. Their “big picture” was mistaken though, and in their panoramic blurriness they mistakenly urged people to become locavores for the sake of the environment, when in fact becoming a locavore might have increased carbon emissions.

Quotation 6—Local foods and carbon footprints

“It is currently impossible to state categorically whether or not local food systems emit fewer [greenhouse gasses] than non-local food systems.”

—

Edwards, Jones, G., L. Mila` i Canals, N. Hounsome, M. Truninger, G. Koerber, B. Hounsome,P. Cross, E.H. York, A. Hospido, K. Plassmann, I.M. Harris, R.T. Edwards, G.A.S. Day, A.D. Tomos, S.J. Cowell and D.L. Jones. 2008. “Testing the Assertion That ‘Local Food is Best’: The Challenges of an Evidence Based Approach.” Trends in Food Science and Technology. 19:265-274.

Parting thoughts

The purpose of this article is not to dissuade the student from attempting to purchase more ethical food. To alter one’s diet in a way that improves the world is a laudable act. What this article seeks to do is to illustrate that our intuition about the morality of certain foods is often wrong. To truly be ethical eaters we must also insist on reading scientific research on food issues as well as train ourselves to think more logical. Don’t abandon intuition, supplement it with the side dishes of science and logic.

Figures

(1) Personal photo.

(2) Original figure.

(3) Source of map shown in figure. Text and arrow were added.

References

(B2) Bailey, Ronald. November 4, 2008. “The Food Miles Mistake.” Reason magazine.

(C1) Coley, David, Mark Howard, and Michael Winter. 2009. “Local food, food miles and carbon emissions: A comparison of farm shop and mass distribution approaches.” Food Policy. 34:150-155.

(L1) Lusk, Jayson L. and F. Bailey Norwood. “The Locavore's Dilemma: Why Pineapples Shouldn't be Grown in North Dakota.” Library of Economics and Liberty. www.econlib.org. January 3, 2011.

(H1) Hume, David. 1742. Essays, Moral Political, and Literary. Eugene F. Miller [editor and translator]. Library of Economics and Liberty. Available at —Lincoln, Abraham. Quoted in: Buchholz, Todd G. 1990. New Ideas From Dead Economists. Plume Publishing: NY, NY. Page 69.

(S1) Saunders, C, A Barber, And G. Taylor. July 2006. Food Miles—Comparative Energy/Emissions Performance of New Zealand’s Agriculture Industry. Lincoln University. Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit. Research report no. 285.